In 1895, the Board of Trustees of Washington University hired the landscape architecture firm of Olmsted, Olmsted & Elliot to develop a preliminary plan for a new campus site at the edge of the city. At that time, Forest Park was indeed a forested park, and the hilltop campus was a site of sharp gullies and savanna-like grasses and trees.

Into this landscape, Olmsted Brothers projected a picturesque campus with a sweeping entry that both followed the contours of the site as well as their longstanding design tropes of meandering paths and jaunty disposition of buildings. But within this pastoral vision, they also set the tone for what would become the defining characteristics of the campus–a set of nested outdoor rooms or courts, arranged orderly along the hilltop site.

Into this landscape, Olmsted Brothers projected a picturesque campus with a sweeping entry that both followed the contours of the site as well as their longstanding design tropes of meandering paths and jaunty disposition of buildings. But within this pastoral vision, they also set the tone for what would become the defining characteristics of the campus–a set of nested outdoor rooms or courts, arranged orderly along the hilltop site. But within four years, having been invited to take part in the final, international competition for the master-plan of the campus, and with the site having doubled in size, the meandering, topographically responsive entry of Olmsted’s preliminary scheme gave way to a centralized plan linking Forest Park and the University. Here, then, lies the fate of this site. Every entry into the competition–from Olmsted to Cope & Stewardson, and from Cass Gilbert to McKim, Meade & White–projected this axis across the contours of the undulating landscape. To think otherwise, it seems, was to give-in to the specificity of place and context. And here, perhaps, lies a prolegomenon to the politics of topography.

But within four years, having been invited to take part in the final, international competition for the master-plan of the campus, and with the site having doubled in size, the meandering, topographically responsive entry of Olmsted’s preliminary scheme gave way to a centralized plan linking Forest Park and the University. Here, then, lies the fate of this site. Every entry into the competition–from Olmsted to Cope & Stewardson, and from Cass Gilbert to McKim, Meade & White–projected this axis across the contours of the undulating landscape. To think otherwise, it seems, was to give-in to the specificity of place and context. And here, perhaps, lies a prolegomenon to the politics of topography.

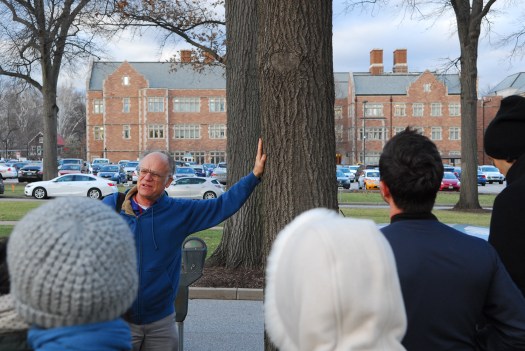

We have been studying the biological functioning and ecological interrelationships of a tree, but they also exist as uniquely social and legal objects in the landscape. For whom does a tree do its work? What work, exactly, is it doing? And who is responsible when it fails? Trees relationship to law, risk, and property confer a unique sort of status to the public nature of ownership, and challenge some of the more abiding categories of boundary definition and maintenance.

We have been studying the biological functioning and ecological interrelationships of a tree, but they also exist as uniquely social and legal objects in the landscape. For whom does a tree do its work? What work, exactly, is it doing? And who is responsible when it fails? Trees relationship to law, risk, and property confer a unique sort of status to the public nature of ownership, and challenge some of the more abiding categories of boundary definition and maintenance.